[Calculus] 3. Series

Definition 3.1 Let \(a_n(n\in\N)\) be a sequence in \(\R\). We say that the series \(\sum_{n=1}^\infty a_n\) converges to a real number \(S\) if \(\lim_{n\to\infty} s_n = S\), where \(s_n := \sum_{j=1}^n a_j = a_1 + \cdots + a_n\) is the n-th partial sum of \(\sum_n a_n\).

If such S exists (or does not exist), we say that the series \(\sum_n a_n\) is convergent (or divergent).

Proposition 3.2 If \(\sum_n a_n\) converges, then \(\lim_{n\to\infty} a_n = 0\).

Proof \(\sum_n a_n\) converges, then \(\lim_{n\to\infty} s_n = S\). By definition of limits, we have \(\lim_{n\to\infty} s_{n+1} = S\) too.

Then \(\lim_{n\to\infty}a_n = \lim_{n\to\infty}(s_{n+1} - s_n) = \lim_{n\to\infty} s_{n+1} - \lim_{n\to\infty} s_n = 0\). □

Definition 3.3 Given a sequence \(a_n(n\in\N)\), we say that

- \(\sum_n a_n\) converges absolutely if \(\sum_n|a_n|\) converges;

- \(\sum_n a_n\) converges conditionally if \(\sum_n|a_n|\) does not converge but \(\sum_{n=1}^\infty a_n\) converges.

Proposition 3.4 If \(\sum_n |a_n|\) converges, then \(\sum_n a_n\) converges.

Proof Let \(s_n = a_1 + \cdots + a_n\), \(\overline{s}_n = |a_1| + \cdots + |a_n|\).

\begin{align*} \sum_n |a_n| < \infty & \Lrarr \lim_{n\to\infty}\overline{s}_n < \infty \\ & \Lrarr \overline{s}_n\text{ is Cauchy} \\ & \Lrarr \forall \epsilon > 0 \exists N\in\N[n > m \ge N \Rarr |\overline{s}_n - \overline{s}_m| < \epsilon] \\ & \Lrarr \forall \epsilon > 0 \exists N\in\N[n \ge N \Rarr ||a_{m+1}| + \cdots + |a_n|| < \epsilon] \\ & \Rarr \forall \epsilon > 0 \exists N\in\N[n \ge N \Rarr |a_{m+1} + \cdots + a_n| < \epsilon] \text{ (By Triangle Inequality)} \\ & \Lrarr \forall \epsilon > 0 \exists N\in\N[n > m \ge N \Rarr |s_n - s_m| < \epsilon] \\ & \Lrarr s_n\text{ is Cauchy} \\ & \Lrarr \lim_{n\to\infty} s_n < \infty \\ & \Lrarr \sum_n a_n < \infty \end{ali□Proposition 3.5 (Comparison test) Let \(a_n, b_n(n\in\N)\) be positive sequences. If \(\lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{a_n}{b_n}\) exists, then

- \(\exists C > 0, N\in\N[n\ge N \Rarr a_n \le Cb_n]\)

- And hence, \(\sum_n b_n < \infty \Rarr \sum_n a_n < \infty\).

Proof Proof 1.

Let \(L := \lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{a_n}{b_n}\). By definition, \(n\ge N\Rarr [|\frac{a_n}{b_n} - L| < \epsilon]\). In particular, \(\frac{a_n}{b_n} < L + \epsilon \Lrarr a_n < (L + \epsilon)b_n\).

Let \(C := L + \epsilon\), then the proof is done.

Equal sign does not matter. If in this case, just adjust the rate \(C\).

Proof 2.

For all \(n\ge N\), consider \(a_1 + \cdots + a_n\).

\begin{align*} a_1 + \cdots + a_N + a_{N+1} + \cdots + a_n & \le a_1 + \cdots + a_N + C(b_{N+1} + \cdots + b_n) \\ & \le a_1 + \cdots + a_N + CM \end{align*}, for some \(M > 0\), since \(\sum_n b_n\) is convergent, and hence is bounded.

Thus the partial sum of \(\sum_n a_n\), \(S_n\) is bounded.

Since \(a_n\) is positive for all \(n\in\N\), \(S_{n+1} -S_n = a_{n+1} > 0\), which means \(S_n\) is increasing.

By Theorem 2.7, \(S_n\) converges, then \(\sum_n a_n\) converges, too. □

Proposition 3.6 (The ratio test) Let \(a_n(n\in\N) \ge 0\). If \(\lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{a_{n+1}}{a_n} < 1\), then

- \(\exists C < 1, N\in\N[n\ge N \Rarr a_{n+1} \le Ca_n]\)

- And hence, \(\sum_n a_n < \infty\).

Proof

(1)

Let \(L := \lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{a_{n+1}}{a_n} < 1\).

For contradiction, suppose for all \(C\in(0,1)\), especially \(C\in(L,1)\), we have \(a_{n+1} \ge C a_n\).

By definition, \(n\ge N\Rarr [|\frac{a_{n+1}}{a_n} - L| < \epsilon]\). Then \((L + \epsilon)a_n > a_{n+1} \ge Ca_n\), i.e., \(\epsilon > C - L\).

Let \(\epsilon = \frac{C - L}{2} > 0\), then \(\frac{C - L}{2} > C - L \Rarr C - L < 0\), which is a contradiction.

Therefore for any \(\epsilon > 0\), \(\exists C < 1, N\in\N[n\ge N \Rarr a_{n+1} \le Ca_n]\).

(2)

For all \(n \ge N\), consider \(S_{n} = a_1 + \cdots + a_N + a_{N+1} + \cdots + a_{n} = F + a_{N+1} + \cdots + a_{n}\).

\begin{align*} S_{n} &= a_1 + \cdots + a_{N} + a_{N+1} + \cdots + a_{n}\\ &\le F + a_N C + \cdots + a_N C^{n-N}\\ &= F + a_N C \frac{ 1 - C^{n-N} }{ 1 - C } \end{align*}Reach limit for both sides, \(\lim_{n\to\infty}S_{n} \le F + a_N C \lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{ 1 - C^{n-N} }{ 1 - C }\), by comparion test, \(\lim_{n\to\infty}S_{n}\) exists, and hence \(\sum a_n\) converges. □

Proposition 3.7 (The root test) Let \(a_n(n\in\N) \ge 0\). If \(\lim_{n\to\infty}(a_n)^{\frac{1}{n}} < 1\), then

- \(\exists C < 1, N\in\N[n\ge N \Rarr a_n \le C^n]\)

- And hence, \(\sum_n a_n < \infty\).

Proof (1)

Let \(L := \lim_{n\to\infty}(a_n)^{\frac{1}{n}} < 1\).

For contradiction, suppose for all \(C\in(0,1)\), especially \(C\in(L,1)\), we have \(a_{n} \ge C^{n}\).

By definition, \(n\ge N\Rarr [|(a_n)^{\frac{1}{n}} - L| < \epsilon]\). Then \(L + \epsilon > a_{n}^{\frac{1}{n}} \ge C\), i.e., \(\epsilon > C - L\).

Like before, we can choose a proper \(\epsilon\) to produce a contradiction.

(2)

For all \(n \ge N\), consider \(S_{n} = a_1 + \cdots + a_N + a_{N+1} + \cdots + a_{n} = F + a_{N+1} + \cdots + a_{n}\).

\begin{align*} S_{n} &= a_1 + \cdots + a_{N} + a_{N+1} + \cdots + a_{n}\\ &\le F + C^{N+1} + \cdots + C^{n}\\ &= F + C^N \frac{ 1 - C^{n-N+1} }{ 1 - C } \end{align*}Reach limit for both sides, \(\lim_{n\to\infty}S_{n} \le F + C^N \lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{ 1 - C^{n-N+1} }{ 1 - C }\), by comparion test, \(\lim_{n\to\infty}S_{n}\) exists, and hence \(\sum a_n\) converges. □

Definition 3.8 A series \(\sum_n a_n\) is an alternating series if \(\exists b_n > 0 (n\in\N)\) such that \(a_n = (-1)^{n-1}b_n\).

Proposition 3.9 (Leibnitz's criterion) If \(\sum_n a_n\) is an alternating series, and \(b_n = |a_n|\) decreases to 0 as \(n\to\infty\). Then \(\sum_n a_n\) converges.

Proof Let \(b_n = (-1)^{n-1}a_n\).

Consider a tail of \(a_n\). \(|a_k + \cdots + a_{k+l}| = |(-1)^k(b_k - b_{k+1} + \cdots + (-1)^lb_{k+l})| = b_k - b_{k+1} + \cdots + (-1)^lb_{k+l}\). Note that \(b_k - b_{k+1} + \cdots + (-1)^lb_{k+l}\) is always positive.

And \[b_k - b_{k+1} + \cdots + (-1)^lb_{k+l} = \begin{cases} b_k - (b_{k+1} - b_{k+2}) - \cdots - (b_{k+l-1} - b_{k+l}) &\text{if } l\text{ is even} \\ b_k - (b_{k+1} - b_{k+2}) - \cdots - (b_{k+l-2} - b_{k+l-1}) - b{k+l} &\text{if } l\text{ is odd} \\ \end{cases} < b_k \] since every terms after \(b_k\) is positive, and \(b_k\) is less than itself substracting finitely many positive terms.

From \(\lim_{n\to\infty}b_n = 0\), then we have

\[ \forall \epsilon > 0 \exists N\in\N [n\ge N \Rarr |b_n| < \epsilon \Rarr |a_n + \cdots + a_{n+l}| < \epsilon] \]

By former proposition, \(\sum_n a_n\) converges. □

Definition 3.10 Given a sequence \(a_n(n\in\N)\), separate all terms into two sequences \(a_{n_1}, a_{n_2},\cdots\) and \(a_{n_1'}, a_{n_2'},\cdots\) with (1) \(n_1 < n_2 < \cdots\) and \(n_1' < n_2' < \cdots\); (2) \(\{n_1,n_2,\cdots\}\cup\{n_1',n_2',\cdots\}=\N\), such that \(a_{n_j}\ge 0(j\in\N)\) and \(a_{n_k'}\le 0(k\in\N)\). Define: \(p_j:=a_{n_j}(j\in\N)\) and \(q_k:=-a_{n_k'}(k\in\N)\).

Proposition 3.11 \(a_n\) converges absolutely iff \(\sum_j p_j < \infty\) and \(\sum_k q_k < \infty\). Moreover, if any side holds, then \(\sum_n |a_n| = \sum_j p_j + \sum_k q_k\) and \(\sum_n a_n = \sum_j p_j - \sum q_k\).

Proof (\(\Rarr\)) Let \(L_1 = \sum_n |a_n|\), and \(L_2 = \sum_n a_n\).

Consider \(p_1 + \cdots + p_j\) for all \(j\in\N\).

Find an index \(n\in\N\) such that \(a_n = p_j\). We claim that \(a_1+\cdots+a_n \le p_1 + \cdots + p_j \le |a_1| + \cdots + |a_n|\).

(Left inequality)

By definition, \(\{p_1,\cdots,p_j\}\sube\{a_1,\cdots,a_n\}\). Besides, there may be some negative terms in \(\{a_1,\cdots,a_n\}\), which means the sum \(a_1+\cdots+a_n \le p_1+\cdots+p_j\) where the equality holds when no negative terms.

(Right inequality)

Similarly, but all the negative terms turn into positive. Therefore the sum can not be less, i.e., \(p_1+\cdots+p_j \le |a_1| + \cdots + |a_n|\) where equality holds when no negative terms.

For any \(\epsilon > 0\), there exists \(N\in\N\) such that when \(n\ge N\)

\[L_2 - \epsilon < a_1+\cdots+a_n \le p_1 + \cdots + p_j \le |a_1| + \cdots + |a_n| < L_1 +\epsilon\]

i.e., sequence \(Sp_j = p_1 + \cdots + p_j\) is bounded, thus \(\sum_j p_j\) is convergent.

Consider \(q_1 + \cdots + q_k\) for all \(k\in\N\).

Find an index \(n\in\N\) such that \(a_n = q_k\). With similar reasons, we claim that

\[- L_1 - \epsilon < -(|a_1| + \cdots + |a_n|) \le q_1 + \cdots + q_k \le a_1+\cdots+a_n < L_2 + \epsilon\]

Then \(Sq_k = q_1 +\cdots + q_k\) is also bounded, and hence \(\sum_k q_k\) is convergent.

(\(\Larr\)) Suppose \(P = \sum_j p_j, Q = \sum_k q_k\).

For any \(\epsilon > 0\), there exists \(N\in\N\) such that

\[\begin{gather*} P - \epsilon < p_1 + \cdots + p_j < P + \epsilon \text{ for all } j\ge N\\ Q - \epsilon < q_1 + \cdots + q_k < Q + \epsilon \text{ for all } k\ge N \end{gather*}\]

(1) Consider \(S_1 = (p_1 + \cdots + p_j) + (q_1 + \cdots + q_k)\). Then \(|S_1 - (P+Q)| < 2\epsilon\).

By definition, we can find an index \(n\in\N\) such that \(|a_1| + \cdots + |a_n| = S_1\). Thus we have \(\sum_n |a_n|\) is convergent to \(P+Q\), which is \(\sum_j p_j + \sum_k q_k\).

(2) Consider \(S_2 = (p_1 + \cdots + p_j) - (q_1 + \cdots + q_k)\). Then \(|S_2 - (P-Q)| < 2\epsilon\).

Still by definition, we can find an index \(m\in\N\) such that \(a_1 + \cdots + a_m = S_2\), and hence \(\sum_n a_n\) is convergent to \(P-Q\), which is \(\sum_j p_j - \sum_k q_k\). □

Proposition 3.12 Give two convergent series \(\sum_n a_n\) and \(\sum_n b_n\), then \(\sum_n (a_b\pm b_n) = \sum_n a_n \pm \sum_n b_n\).

Proof Assume that \(\sum_n a_n = S_1, \sum_n b_n = S_2\), and let \(c_n := a_n \pm b_n\). Then \(\forall \epsilon > 0 \exists N\in\N[n \ge N \Rarr |a_1 + \cdots + a_n - S_1| < \epsilon \land |b_1 + \cdots + b_n - S_2| < \epsilon]\).

The partial sum of \(c_n\):

\[\begin{align*} c_1 \pm \cdots \pm c_n & = (a_1 + b_1) \pm \cdots \pm (a_n + b_n) \\ & = (a_1 + \cdots + a_n) \pm (b_1 + \cdots + b_n) \\ \end{align*}\]

Therefore, for all \(n \ge N\), we have

\[\begin{gather*} S_1 \pm S_2 - 2\epsilon < c_1 + \cdots \pm c_n < S_1 \pm S_2 + 2\epsilon \\ |c_1 + \cdots \pm c_n - (S_1 \pm S_2)| < 2\epsilon \end{gather*}\]

i.e., \(\sum_n (a_n \pm b_n)\) exists, which equals to \(\sum_n a_n \pm \sum_n b_n\). □

Definition 3.13 (Rearrangement) Given a bijective mapping \(m:\N\to\N,n\mapsto m(n)\). We call \(a_{m(n)}\) a rearrangement of a series \(a_n\)

Lemma 3.14 If \(\sum_n a_n\) converges, and \(a_n \ge 0\) for all \(n\in\N\). Then \(s_n = a_1 + \cdots + a_n\) is bounded.

Proof Since \(\sum_n a_n\) converges, to L say, we have \(\forall \epsilon > 0 \exists N\in\N[ n \ge N \Rarr |s_n - L| < \epsilon]\).

For deducing a contradiction, suppose \(s_n\) is unbounded. Then \(\exists N'\in\N [s_{N'} > L + \epsilon]\).

Case I. \(N' \ge N\).

We then have \(a_1 + \cdots + a_{N'} > L + \epsilon\). This contraidcts to the definition of limits

Case II. \(N' < N\).

Then \(a_1 + \cdots + a_{N'} > L + \epsilon > a_1 + \cdots + a_{N'} + a_{N' + 1} + \cdots + a_n\), i.e., \(a_{N'+1} + \cdots + a_n < 0\), a contradiction.

Therefore, \(s_n\) is bounded. □

Lemma 3.15 If \(\sum_n a_n\) is convergent and for all \(n\in\N\), \(a_n \ge 0\), then \(\sum_m a_{n(m)} = \sum_n a_n\) where \(a_{n(m)}(m\in\N)\) is a rearrangement of \(a_n\).

Proof Let \(A = \{a_{n_1} + \cdots + a_{n_k} | n_1 < \cdots < n_k \land k\in\N\}, B = \{a_1 + \cdots + a_n | n\in\N\}\), and \(s_n := a_1 + \cdots + a_n\).

Firstly, \(B\sube A\). Then \(\sup B \le \sup A\). (Obviously)

By the former lemma, \(s_n\) is bounded. \(s_n\) is increasingly monotone, by Theorem 2.7, \(\sum_n a_n = \lim_{n\to\infty}s_n = \sup B\).

We can always find a \(m\in\N\) such that \(m = n_k\), then \(a_{n_1} + \cdots + a_{n_k} \le a_1 + \cdots + a_m\), where equality holds if \(k=m\).

In other words, \(\forall a\in A, \exists b\in B[a < b]\), then \(\sup A \le \sup B\).(Obviously)

Therefore, \(\sup\{a_{n_1} + \cdots + a_{n_k} | n_1 < \cdots < n_k \land k\in\N\} = \sup A = \sup B = \sum_n a_n\).

Consider \(C=\{a_{n(1)} + \cdots + a_{n(m)} | m\in\N\}\), which is the set of all the partial sums of that rearrangement \(a_{n(m)}\). \(C\sube A \Rarr \sup C = \sup A\) with the almost same reason. Then \(C\) is bounded, by Theorem 2.7, \(\lim_{n\to\infty}(a_{n(1)} + \cdots + a_{n(m)}) = \sup \{a_{n(1)} + \cdots + a_{n(m)} | m\in\N\} = \sup A = \sum_n a_n\). □

Theorem 3.16 (Dirichlet's rearrangement theorem) If \(\sum_n a_n\) converges absolutely, then for every rearrangement \(a_{n(m)}(m\in\N)\) of \(a_n(n\in\N)\), we have \(\sum_{m=1}^\infty a_{n(m)} = \sum_{n=1}^\infty a_n\).

Proof By Proposition 3.11, \(\sum_n a_n\) is absolutely convergent, the \(\sum_j p_j\) and \(\sum_k q_k\) exists too.

Rearranging \(a_n\) means \(p_j\) and \(q_k\) are also rearranged. By Lemma 3.15, \(p_{j(m)}\) and \(q_{k(m)}\) of the rearrangement \(a_{n(m)}\) will not change since they are both positive sequences.

By Proposition 3.11, again, the series \(\sum_m a_n(m) = \sum p_{j(m)} - \sum q_{k(m)} = \sum p_j - \sum q_k = \sum_n a_n\). □

Lemma 3.17 Given a conditionally convergent series \(\sum_n a_n\), divide \(a_n(n\in\N)\) into positive subsequence \(p_j(j\in\N)\) and negative subsequence \(q_k(k\in\N)\), then:

- \(\sum_j p_j = \infty\) and \(\sum_k q_k=\infty\);

- \(\lim_{j\to\infty}p_j = \lim_{k\to\infty}q_k = 0\).

Proof Proof 1.

For contradiction, suppose that \(\sum_j p_j < \infty \lor \sum_k q_k\).

If \(\sum_j p_j\) and \(\sum_k q_k\) both exist, then by Proposition 3.11, \(\sum_n a_n\) converges absolutely. This is not mentioned.

Thus we have to assume one of them converges exactly. Without loss of generality, suppose that \(\sum_j p_j < \infty \land \sum_k q_k = \infty\).

Let \(\sum_n a_n = L, \sum_j p_j = P\). For any \(\epsilon > 0\), there exists a big enough \(N\in\N\), such that

\[\big[n\ge N \Rarr |a_1 + \cdots + a_n - L| < \epsilon \land j\ge N \Rarr |p_1 + \cdots + p_j - P| < \epsilon\big]\]

where \(a_1 + \cdots + a_n = p_1 + \cdots + p_j + q_1 + \cdots + q_k\).

\[P - \epsilon < p_1 + \cdots + p_j < P + \epsilon \\ q_1 + \cdots + q_k + P - \epsilon < p_1 + \cdots + p_j + q_1 + \cdots + q_k < q_1 + \cdots + q_k + P + \epsilon \\ \begin{cases} P - \epsilon + q_1 + \cdots + q_k < L + \epsilon \\ L - \epsilon < q_1 + \cdots + q_k + P + \epsilon \end{cases} \\ L - P - 2\epsilon < q_1 + \cdots + q_k < L - P + 2\epsilon\]

i.e., \(\sum_k q_k\) converges to \(L - P\), which contradicts to the assumption.

Therefore, \(\sum_j p_j\) and \(\sum_k q_k\) are both divergent.

Proof 2.

By Proposition 3.2, for any \(\epsilon > 0\), there exists a \(N\in \N\), such that \(n\ge N \Rarr |a_n| < \epsilon\).

Let \(a_1 + \cdots + a_N = p_1 + \cdots + p_J - (q_1 + \cdots + q_K)\), where \(J,K\in\N\). Then

\[\begin{gather*} j \ge J \Rarr |p_J| < \epsilon \\ k \ge K \Rarr |q_K| < \epsilon \end{gather*}\] □

Theorem 3.18 (Riemann's rearrangement theorem) If \(\sum_n a_n\) converges conditionally, then for every \(L\in\R\) there exists a rearrangement \(a_{n(m)}(m\in\N)\) of \(a_n(n\in\N)\) such that \(\sum_{m=1}^\infty a_{n(m)} = L\).

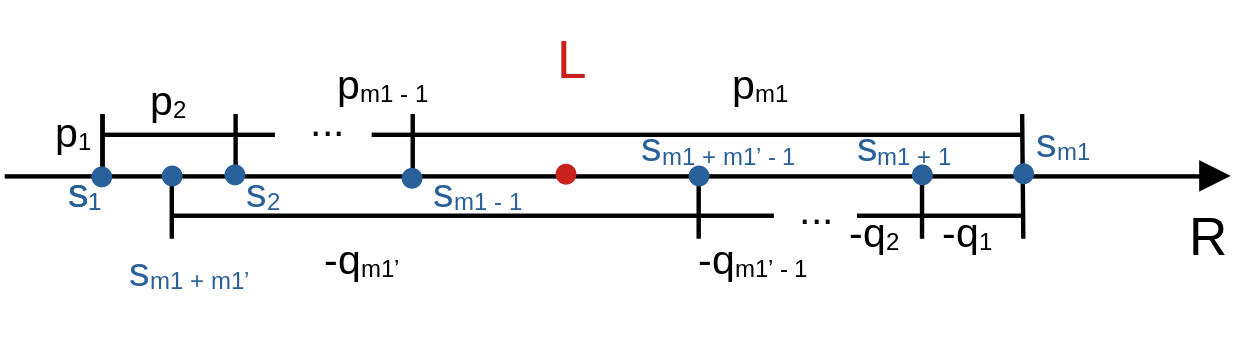

Notation: \(sp_n = p_1 + \cdots + p_n, sq_n = q_1 + \cdots + q_n\), \(s_n\) is the partial sum of rearrangemnt.

Firstly from positive terms of \(a_n\), choose a beginning, say \(p_1\) in the left-side of \(L\). By Lemma 3.17, \(sp_n\) is unbounded, therefore, we can find a index \(m_1\), such that \(s_{m_1} = sp_{m_1} > L\).

Then from negative terms of \(a_n\), we choose \(q_1\), such that we can get close to \(L\). \(sq_n\) is also unbounded, then we can find a index \(m_1'\), such that \(s_{m_1 + m_1'} = sp_{m_1} - sq_{m_1'}\).

Repeat above operations. Our goal is to show: \(\lim_{n\to\infty} s_n = L\).

Drop the figure, we can use pure symbols to demonstrate that.

There exist nutural numbers \(m_1 < m_2 < \cdots\) and \(m_1' < m_2' < \cdots\), where \(m_j\) is the j-th time when the partial sum \(s_n\) is greater than \(L\), and \(m_k'\) is the k-th time when partial sum \(s_n\) is less than \(L\).

Note that:

- the index of \(m_j\) is exactly greater one than or equal to \(m_k'\), i.e., for \(l\in\N\), the indexes are like \(m_l, m_{l-1}'\) or \(m_l, m_l'\).

- \(m_0,m_0'\) means the jump has not begun yet.

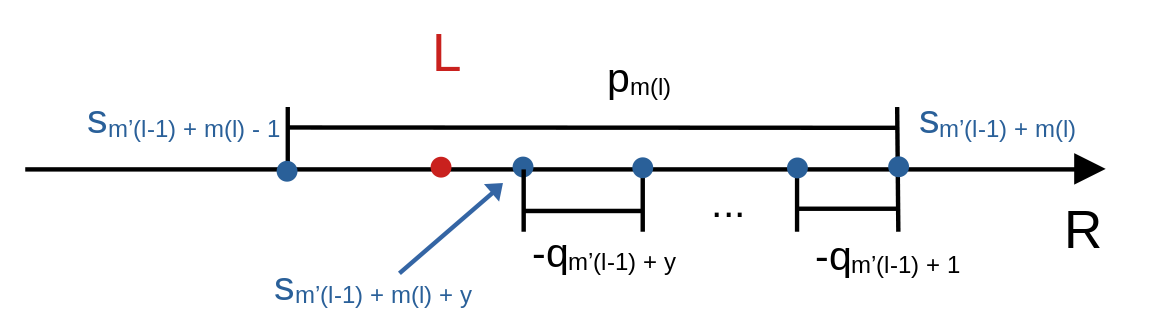

Consider the general case.

After jumping the next step \(p_{m_l}\), the beginning point \(s_{m_{l-1}' + m_l -1}\) will over \(L\) to \(s_{m_{l-1}' + m_l}\), then start to jumping back. Suppose it has jumped back \(t\) times, but not back over \(L\). We have

\[\left|s_{m_{l-1}' + m_l + y}\right| < q_{m_l}\]

if \(0 \le y < m_l' - m_{l-1}'\). i.e., the total length of backward jumps will less than the last forward jump when the point is still on the right-side of \(L\).

Similarly, \(\left|s_{m_l}' + m_l + x\right| < q_{m_l'}\) if \(0 \le x < m_{l+1} - m_l\).

By Lemma 3.17, \(\forall \epsilon > 0 \exists N_0 \in\N[l\ge N_0 \Rarr p_{m_l} < \epsilon \land q_{m_l'} < \epsilon]\).

Let \(N = m_{N_0 -1}' + m_{N_0}\). Then \(n\ge N \Rarr |s_n - L| < \epsilon\). □

Proposition 3.19 Let \(\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n\) and \(\sum_{n=0}^\infty b_n\) both converge absolutely, and \(c_n := a_n b_0 + \cdots + a_0 b_n = \sum_{\substack{j+k = n\\j,k\ge 0}} a_j b_k\). Then \(\sum_n |c_n| < \infty\) and \(\sum_{n=0}^\infty c_n = \left(\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n\right)\left(\sum_{n=0}^\infty b_n\right)\).

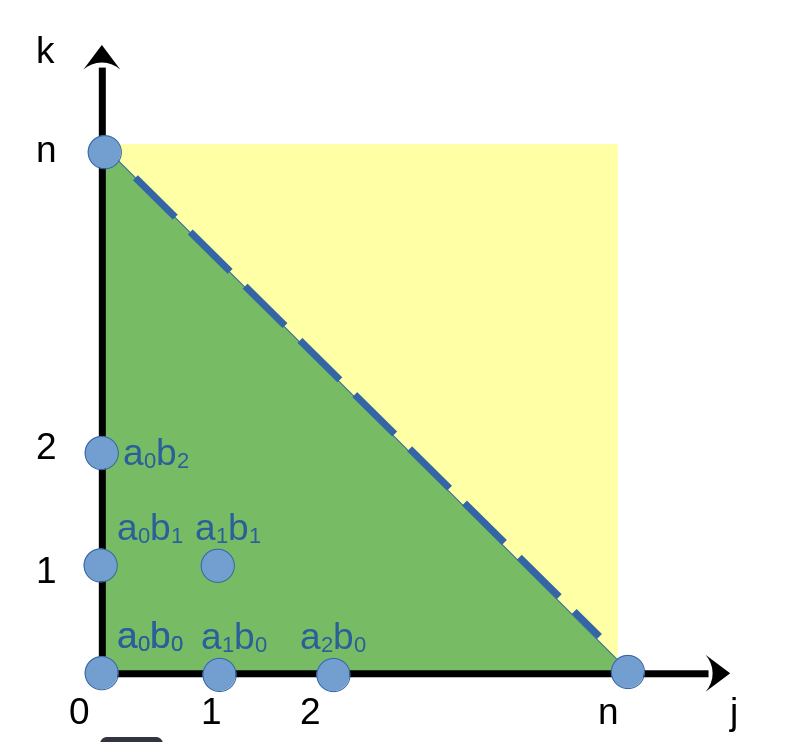

Proof \[\begin{align*}|c_0| + |c_n| & = \sum_{i=0}^n \left|\sum_{\substack{j+k=i\\j,k\ge 0}}a_jb_k\right|\\ & \le \sum_{i=0}^n\sum_{\substack{j+k=i\\j,k\ge 0}} |a_j||b_k| \text{ (By Triangle Inequality)} \\ & \le \left(\sum_{j=0}^n |a_j|\right)\left(\sum_{k=0}^n |b_k|\right) \text{the area of triangle is less than the rectangle in the figure.} \\ & \le M\cdot N \text{these two series are bounded} \end{align*}\]

Thus \(\sum_n |c_n|\) converges.

Let \(A_n := a_0 + \cdots + a_n, B_n := b_0 + \cdots + b_n, C_n := c_0 + \cdots + c_n\).

We claim that \(\lim_{n\to\infty}(A_n B_n - C_n) = 0\).

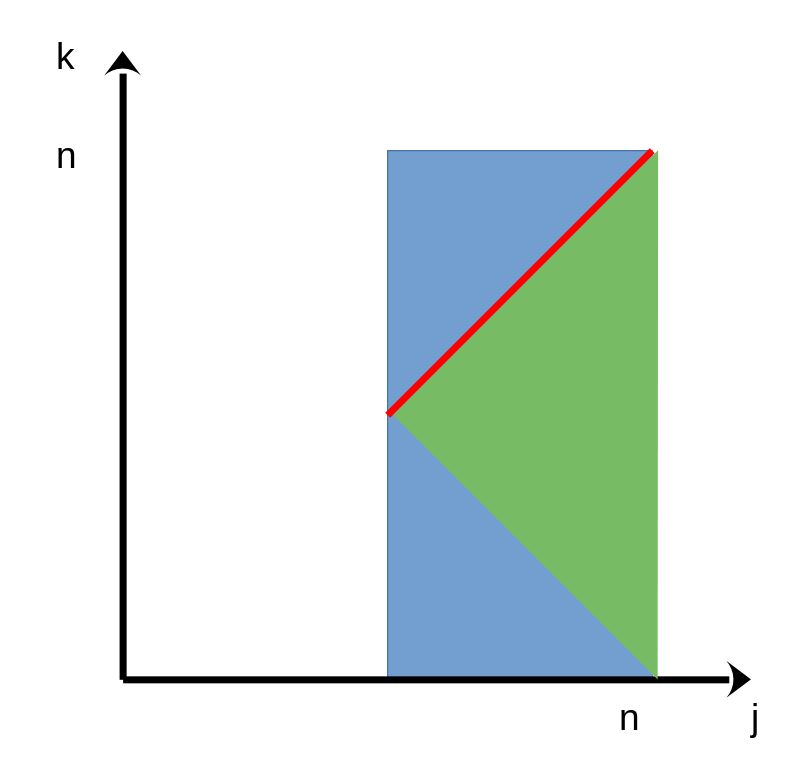

In above figure, \(A_n B_n - C_n\) is the rest area of the rectangle subtracting the triangle. Thus \(|A_n B_n - C_n| \le \sum_{\substack{j+k > n\\0\le j,k\le n}}|a_jb_k|\).

The rest triangle can be separated into two part, each part is controled by a rectangle as following fingure.

Therefore

\[|A_n B_n - C_n| \le \left(\sum_{j=\lfloor{\frac{n}{2}}}^n |a_j|\right) \left(\sum_{k=0}^n |b_k|\right) + \left(\sum_{j=0}^n |a_j|\right) \left(\sum_{k=\lfloor{\frac{n}{2}}}^n |b_k|\right)\]

\(\sum_{j=0}^n |a_j|\) and \(\sum_{k=0}^n |b_k|\) are bounded. \(\left(\sum_{j=\lfloor{\frac{n}{2}}}^n |a_j|\right)\) and \(\left(\sum_{k=\lfloor{\frac{n}{2}}}^n |b_k|\right)\) trends to 0 as \(n\to\infty\) (since they are tail of the absolutely convergent series).

i.e., \(0 \le |A_n B_n - C_n| \le 0\), and hence \(\sum_{n=0}^\infty c_n = \left(\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n\right)\left(\sum_{n=0}^\infty b_n\right)\) □

Theorem 3.20 If \(\sum_{n=1}^\infty a_n\) and \(\sum_{n=1}^\infty b_n\) converges absolutely, \(\N\to\N\times\N: n\mapsto [j(n), k(n)]\) is bijection, and \(c_n := a_{j(n)} b_{k(n)} (n\in\N)\). Then \(\sum_n |c_n|\) exists and \(\sum_n |c_n| = \left(\sum_n a_n\right) \left(\sum_n b_n\right)\).

Proof For any \(n\in\N\), let \(l = \max\{j(1), \cdots, j(n), k(1), \cdots, k(n)\}\). Then

\[\begin{align*}|c_1| + \cdots + |c_n| & = |a_{j(1)}b_{k(1)}| + \cdots |a_{j(n)}b_{k(n)}| \\ & \le \left(\sum_{j=1}^l |a_j|\right)\left(\sum_{k=1}^l |b_k|\right) \text{area of rectangle is greater than triangle} \\ & \le M\cdot N \text{(bounded)} \end{align*}\]

for some \(M,N\). Thus \(\sum_n c_n\) is absolutely convergent.

Let \(A_n = \sum_{i=1}^n a_i,B_n = \sum_{i=1}^n b_i,C_n = \sum_{i=1}^n c_i\).

\[A_n B_n = (a_1 + \cdots + a_n) (b_1 + \cdots + b_n) = \sum_{1\le j,k\le n} a_j b_k\]

Replace the bijection by:

\[\begin{matrix} \vdots & & & & \\ 16 & 15 & 14 & 13 & \\ 9 & 8 & 7 & 12 & \\ 4 & 3 & 6 & 11 & \\ 1 & 2 & 5 & 10 & \cdots \end{matrix}\]

Then we have \(A_n B_n = C_{n^2}\), and hence \(\lim_{n\to\infty} A_n B_n = \lim_{n\to\infty} C_{n^2} = \lim_{n\to\infty} C_{n}\). □